HOITINES POT’ESTE CHAIRETE!

Γλώσσα πρωτότυπου κειμένου: Αγγλικά

Rrose Sélavy, the feminine alter ego of Marcel Duchamp, is a phonetic play on words of the French Eros, c’est la vie that also reads as arroser la vie (translation: to make a toast to life) in the tradition of Dada sound poetry. Rrose Sélavy, Duchamp dressed as a woman, posed as a Hollywood star for artist friend Man Ray for a photography series in the 1920s, a century ago. This playful collaborative practice could be considered a foreshadowing, or better yet a precursor of the discourse that took off years later, concerning postmodern queer studies and their gender identity politics. Perhaps what is even more relevant to this article would be how Duchamp and Man Ray articulated the objectification of the artist’s subjectivity. Portraits of Rrose Sélavy acted as the acknowledgment and legitimation of a culture in which the artist’s image becomes the focal point, the artwork itself, elevating him or her to the status of a celebrity.

Maria Kriara (b. 1982), an architect and PhD candidate in the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki has staged three solo shows until now and participated in several distinguished group exhibitions, including at the Venice Architecture Biennale (2006), Tinguely Museum, Basel (2013), 5th Thessaloniki Biennial (2015) and Kunstverein Herdecke (2017). Her solo show entitled Cogito (.) or I think therefore I am…a Rhinoceros (2014) referenced Albrecht Dürer’s 1515 infamous woodcutting print illustrating the animal that the artist himself had never seen.

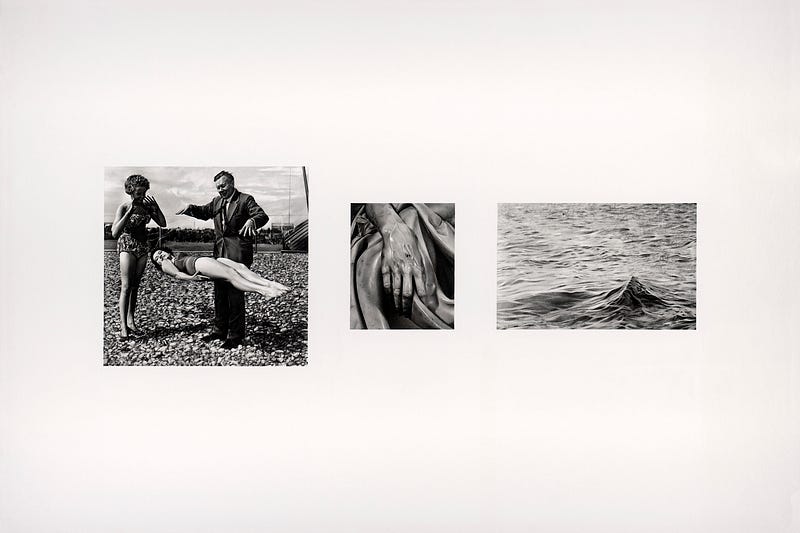

The exhibition consisted mostly of pencil drawing pairings, diptychs and triptychs of seemingly unrelated images that create a type of story-telling reminiscent of the disorienting but also liberating fragmentation of instagram scrolling which fosters the dialogue of multiple synchronous subjectivities and their respective projected selves. Endless ahistorical meta-texts are triggered by the observation of Kriara’s triptychs. Most of these readings require an encyclopedic knowledge that is today easily accessible via Wikipedia and the obsessive investigation of hyperlinks. The curatorial character of their composition reveals the limitless potential of intertextuality in the digital age or simply put, an everyday google image search. Whitechapel Gallery’s curator, Emily Butler writes in the exhibition text that “Kriara is asking us to think about how these visuals are perceived once released back into the world in a wholly different context”. Each work individually reveals a drawing ability of such rarity that one cannot help but wonder if they are actually black and white scans of Xerox copied printouts. However, their Benjamin-defined aura makes these pencil drawings read as a hyper high-definition version of Man Ray’s photographs of Rrose Sélavy.

Kriara’s latest solo show, Pawnshop, 2017, a title that occurred after the 9 years of crisis in Greece that conditioned the widespread re-appearance of pawnshop transactions, was a simulation of these dynamics in the spatial context of the gallery. In an interview Kriara states: “the very moment a certain object passes through a pawnshop’s threshold it is immediately stripped of its previous connotations and turns into a commodity that is being reevaluated almost strictly according to, either it’s material value, or it’s utilitarian capacity.[1]” Such an attempt urged a re-consideration of the nostalgia assigned to personal or even historical memorabilia and the posing of yet another rhetorical question: “what is worth keeping?”

This ontological quest is depicted in a series of pencil drawings, digital prints, including text-based work, processed newspaper pages, a neon-light installation and even an audio piece in loop. The aura of the unique artwork seems to have turned into a non-issue as traditional drawing is curated to equally co-exist with mediated reproductions of various sorts. The most prevalent work in the space was the audio loop repeating the words: “Hoitines pot’este chairete! Eirēnikōs pros philous elēlythamen philoi” (ancient Greek for: Greetings to you, whoever you are! We come in friendship to those who are friends). The sound-quote is the Greek contribution recorded in 1977 for a time capsule that NASA sent off to interstellar space on the Voyager spacecraft in hope to communicate the diversity of life and culture on earth to extraterrestrial life. President Jimmy Carter said of the purposes of this time capsule: “We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours”. The time capsule, including the rather puzzling ancient Greek utterance as the sole representation of Greekness, already travelling for over 40 years, is estimated to outlive human civilization and earth’s lifespan. Kriara mentions about this particular work: “it’s not just her own nostalgia and complex identity this particular Southern European country has to deal with, but also the nostalgia of others, and both old and newly constructed mythologies they project, or sometimes force, on her”.

As I write this text a single word keeps re-entering my mind, almost compulsively: the first part of Maria Kriara’s exhibition title: Cogito (.) the René Descartes Latin half-quote and the unmentioned, but implied, second half: ergo sum. The cogito: I think, therefore I am, a pillar of Western philosophy and the foundation of knowledge production, acts as the reassurance that thought, including doubt, even the doubt of one’s own existence, is the proof of the reality of one’s own mind. In other words, a self with the capacity of a mind is a prerequisite for and evidence of existence. Brain in a vat is a rather elemental thought experiment used in philosophy studies. It hypothesizes that “an entity (e.g. a machine) might remove someone’s brain from their body, suspend it in a vat with life-sustaining liquid and connect its neurons by wires to a supercomputer”. The computer then would “simulate reality for the disembodied brain which would go on to have perfectly normal consciousness and experiences” as if it were still existing in a physical body. The purpose is to make one wonder if and how corporeality is necessary for existence. Brain in a vat has been widely appropriated in science fiction cultural texts.

If Man Ray’s portraits of Rrose Sélavy exposed the objectification of the artistic subjectivity, could Maria Kriara’s pronounced ellipsis of “ergo sum” with its replacement by a full-stop in parenthesis for her show’s title, be manifesting its subsequent dematerialization? Could Maria Kriara be a Rrose Sélavy of the artistic subjectivity in the digital age? Has the identity of the artist morphed from celebrity to inexistence?

For the purposes of this article I was asked to interview Maria Kriara. As she is based in a different city from me, the discussion would have to take place via skype. Due to several, quite real practical issues, mostly related to time and our inability to synchronize in real life, I instead preferred to email her the questionnaire. Ultimately, I decided to limit the interview to a single question: Do you exist?

Evita Tsokanta is an art historian based in Athens who works as a writer, educator and an independent exhibition-maker. She lectures on curatorial practices and contemporary Greek art for the Columbia University Athens Curatorial Summer Program and Arcadia University College of Global Studies. She has contributed to several exhibition catalogues and journals and completed a Goethe Institute writing residency in Leipzig, Halle 14.

[1] https://www.yatzer.com/maria-kriara?fbclid=IwAR3mVTQ5nHDXQ0wFmx8RAgdKeFR8CRzq4bsXfX46Lw4acstYotbTBIOgs_s