STEFANIA STROUZA: OTHERING TIME THROUGH SCULPTURAL GESTURES

Γλώσσα πρωτότυπου κειμένου: Αγγλικά

“I step back from someone who is not yet there and, a millennium in advance, bowing to his spirit.”

(Heinrich von Kleist — quoted by Martin Heidegger)

In one of the most influential works of philosophy of the XX century, Being and Time, Martin Heidegger describes a phenomenon he calls “Temporal Ecstasy”. To give a full analysis of what he meant would require more time and knowledge I can offer in this text, however, I saw glimpses of a just that when I found myself recently going back to Stefania Strouza’s “212Medea”, a work I had the pleasure to follow from its very genesis amid the psychological challenges of the first lock down.

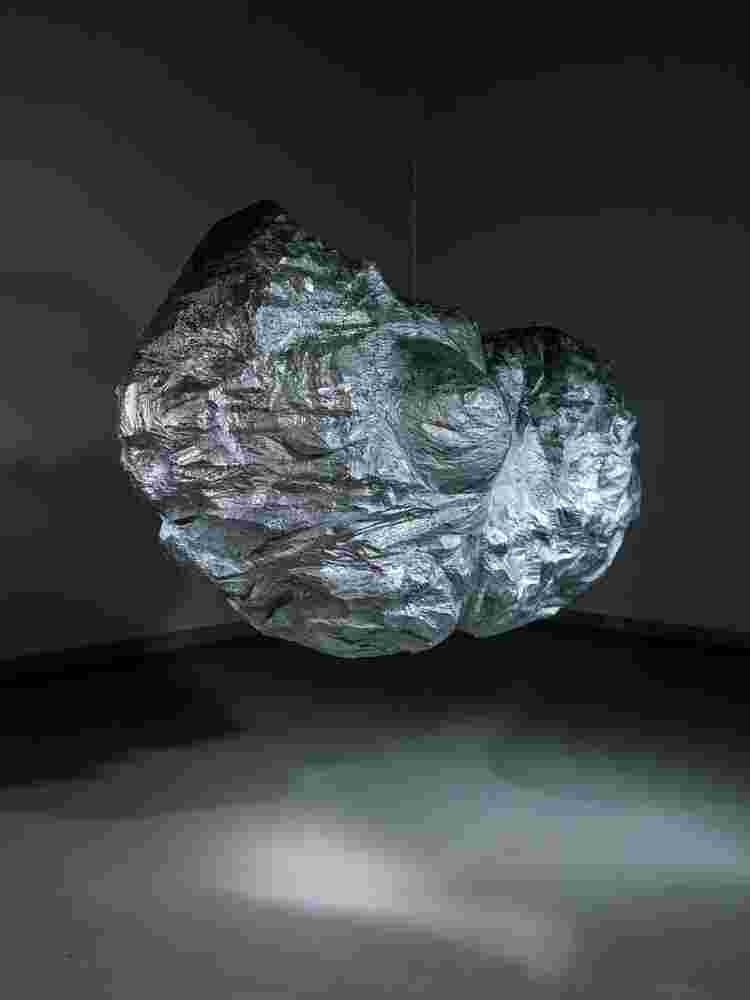

In short, the term describes a moment of being “outside oneself” in relation to time, a moment in which we can see time, not as a linear transition between birth and death but as an element on its own which allows us to unfold our “being in the world”. The asteroid, produced and frozen in its threatening position posing a mortal danger to our very existence on the planet, becomes the materialisation of time for the viewer. It is a gesture rendering time a physical element we can observe, something we are forced to reconceive and deal with rather than accept as a given measure.

212Medea (perpetual silence prevails in the empty space of capital) — as its full title reads — is not just a representation of this threat. It is a gesture which leads us, maybe even urges us, to think of the role of the Other, the role of the natural juxtaposed to our human condition and demands an answer from us as to whether this separation is still something worthy of notice and how we position ourselves in it. It is a work which both stands out for its visual impact and yet fits perfectly into Strouza’s long term research on othering time, on ways to question the role we assign objects as markers of its presence dividing ancient, old, present, and future eras.

Through a delicate and very personal material research, her works acquire characteristics which create a tension between natural and artificial, heavy and light, rough and smooth elements. These juxtapositions however are not an attempt to dissimulate their characteristics, nor do they have an intention of deceiving the viewers. In fact, often the forms created by Strouza let the material transpire in a conscious attempt to have the viewer create new associations, new understanding of the ways we perceive sculptural objects and their own relation to time. The material sensitivity is, in her own words, partially a result of her studies in architecture which have had a great influence in her work. Something I found especially fitting if we think of projects like The Condition of (Im)possibility, presented first in Edinburgh and later at the 6th Biennale in Thessaloniki. An homage to Bruce Nauman and a bridge to Gilles Clement’s Third Landscape, the work encapsules the attempt of Strouza to reflect on and create in-between spaces (and forms) through which we can reflect on our dasein.

212Medea unfolds several themes key to understanding Strouza’s fascination towards the iconic anti-heroin (leading also to her current PhD research on the mythical Colchian princess) first mentioned in Hesiod but brought to life by Euripides and crucially for her own research, movingly adapted by Pasolini in his 1969 film with the same title. Medea for Strouza is far from being only the destructive force we face through the asteroid much more, her figure becomes a tool to investigate the relation between the rational and irrational, science and nature, feminine and masculine world, and of course most of all otherness. This last aspect might, more than anything, resonate in Strouza’s works, something which indeed caught my attention from our very first dialogue in which we talked mostly about “She of the Jade Skirt”, a body of work she produced in connection to a residency in Mexico City. In this series, I could see how her interest in architecture and urbanism merge and interweave with myths. How these worlds can be brought together to create critical narratives challenging patriarchal world structures.

Through observing the works and listening to Strouza’s arguments I could feel Mexico City, with its frantic and unstoppable development smothering Chalchiuhtlicue, ancient goddess of fertility and rivers, who is now exerting her revenge by slowly sinking the city. While formally, much like in 212Medea, it is the material research which attracted me to this series, it was the feeling of otherness evoked by it that became the centre of our dialogue. What I struck me was how the work was able to conjure a deep sense of time through materials which were neither what I could have expected nor used as a simulation.

They were “other”, much like Strouza in our discussion, described her being “other” within a specific context but also towards the work itself. Not in a dissociative manner but in a very intimate and conscious way allowing the work to be other from and yet mediated by her. The works were a medium to talk about her own position within the (her)stories she evokes, a portal to a space in which time and matter are other from us as much as they are artificial, a window into her own state of mind trying to grasp a sense of time and the world which feels long lost. A sensation which emerges as an attempt of our mind to create an empathy towards the world around us, especially when we find ourselves in lands we feel foreign to. I wonder if it is something we need in order to understand our own position in the world, our own “being there”, dasein…

Christian Oxenius is a German-Italian independent curator, author and researcher living between Athens and Istanbul. His academic background in sociology and urban studies led him to pursue a PhD at the University of Liverpool on biennials as institutional model, during the course of which he established collaborations with Athens, Liverpool and Istanbul Biennial; during this period, he developed a particular interest in artists’ communities and storytelling. His research into experimental writing on art has resulted in a number of exhibitions and publications of international relevance.