LINGERING IMAGES

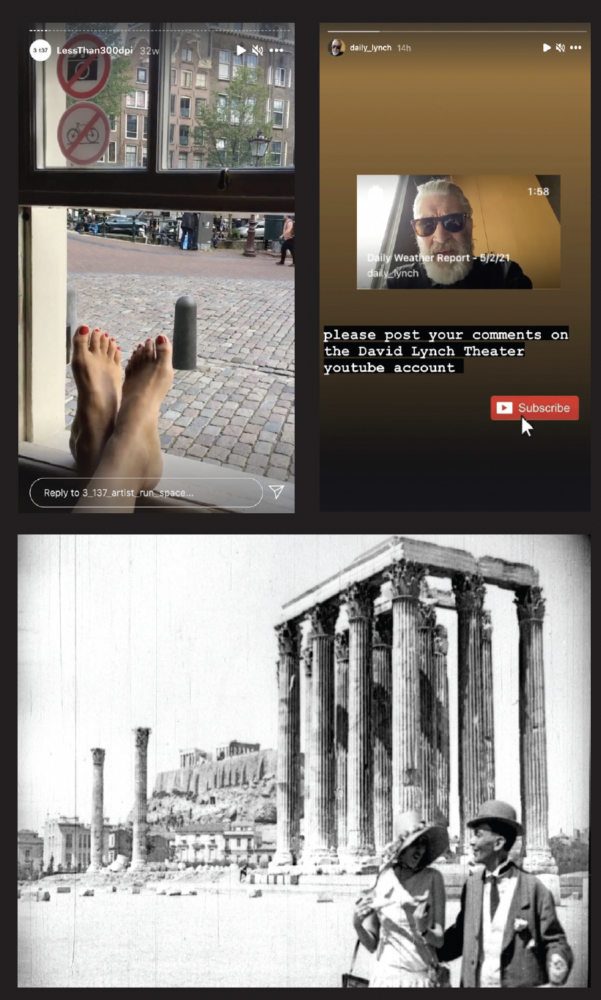

“Good morning. It’s April 9, 2021, and if you can believe it, it’s a Friday once again. Here in L.A., another clear, sunny morning, very still right now. 54 degrees Fahrenheit, around 12 Celsius.” David Lynch’s face is illuminated by a tall window to his side as he peers into the camera through dark sunglasses, sporting a scraggly white beard. I’m watching his daily weather report, which he has posted diligently online since mid-August 2020. I scroll through the grid of images, and his face stares back at me. Though he wears the same sunglasses and black button-down shirt, occasional differences betray the passage of time: a glimpse of green foliage through the window, a scruffy chin. Like all of us, he has been counting the days like a prisoner, observing the world from the confines of his home. His cinematic vision, limited to the same space, is distilled into a visual diary.

In the past year, the moving image has swarmed evermore from cinemas to desktops, phones and televisions. Lapsing into the assurances of routine and daily ritual, we have become obsessive viewers and chroniclers ourselves. We digest the daily primetime COVID-19 news bulletins announced by a task force of health experts; videos capturing scenes of police brutality in central Athens ricochet widely across social media sending protestors to the streets; we text the government status updates on our location each time we head to the supermarket, or outside for a breath of air. As I wait for the world to open up, I think back on the constant online continuum of presentations, art events, screenings and webinars I participated in. Many of them sought to transfer some sort of physical experience into the digital realm without much thought as to how or why, and without proposing new forms of production. But amidst this static there were small moments provoked by a desire to communicate, like Lynch’s weather report, that pushed me to think about the possibilities presented by online platforms for vital and collective viewership.

Less than 300 dpi, an Instagram exhibition of 15 second cine-tracts commissioned by the Athenian artist-run space 3137, was conceived before the onset of COVID-19; by the time it took place in the fall of 2020, its choice of medium had proved prescient, channeling the cliché of our increasingly digital world into a polyphonic, immediate document of the times. Penelope Koliopoulou’s contribution includes a playful inversion of the voyeuristic gaze in Amsterdam’s red light district, where “lads”, filmed from window sills and balconies become the subject of attention. Presented in quick succession, Eva Stefani’s video portraits of her mother are filmed at arm’s reach while her exuberant gaze and performative gestures fill the frame in a precious distillation of affection. The eight individual works, all presented as Instagram stories, play out over the exhibition’s duration as a frenetic, intermittent and ephemeral film, re-envisioning the mundane social media scroll as a space for focused acts of testimony.

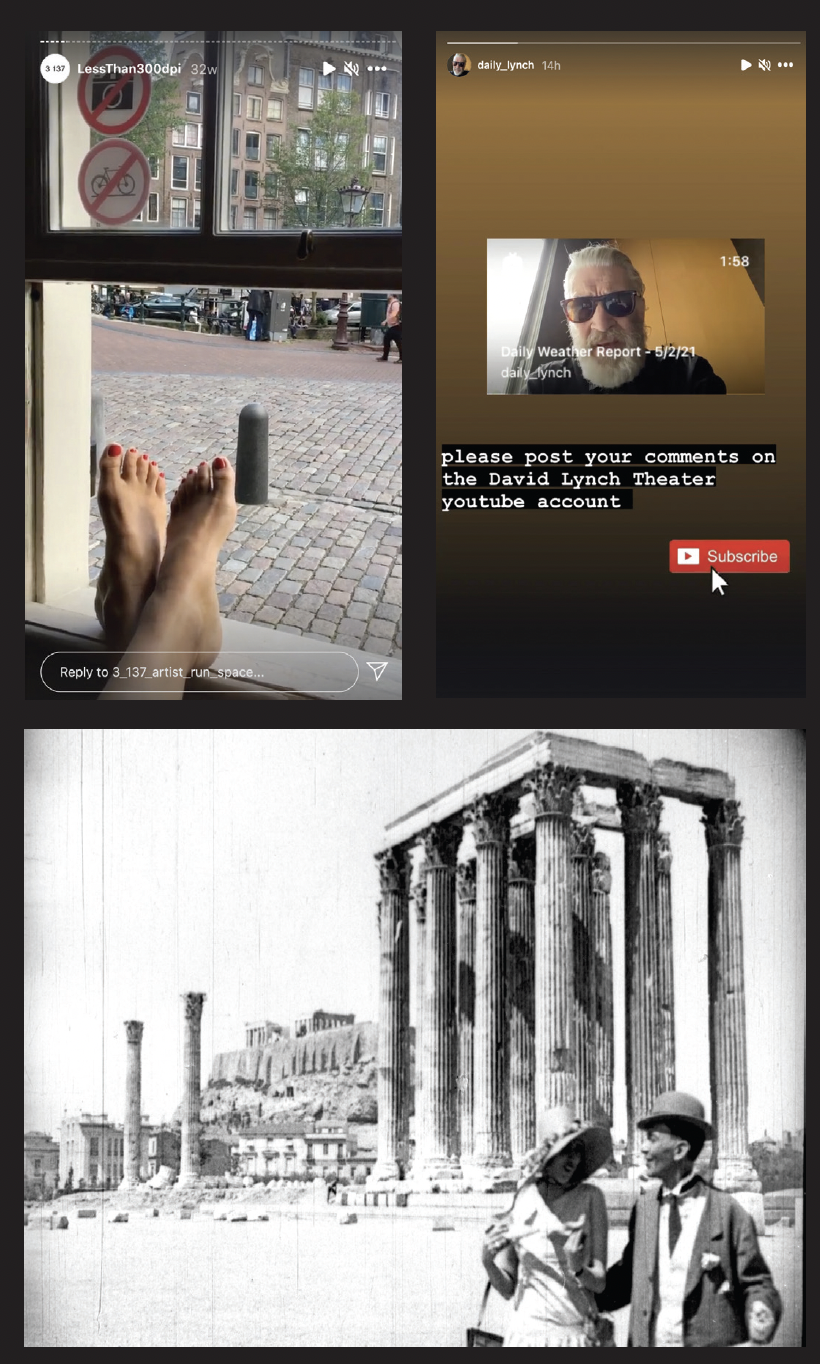

Films and archival materials previously inaccessible to an online audience also became more widely available. One such gem, released by the Greek Film Archive, is Joseph Hepp’s short comedy Villar’s Adventures (1924), the earliest Greek fiction film salvaged in its entirety. In it we follow the exploits of a famed popular comedian of the era who seeks to win over a young lady’s heart as he tours the Odeon of Herodes Atticus and dances to Dixieland in a dusty and undeveloped Faliro: a playful antidote to the empty streets of pandemic-era Athens.

Archival images have kept me close company this past year, both as historical reminders of eras outside my own, and as resources for imagining new narratives. Peripheral Vision, a workshop conceived by me and my programming colleagues at the Syros International Film Festival, held in collaboration with filmmaker Tamer El Said and the Cairo Cimatheque, was initially slated to take place during the summer 2020 edition of the festival. Inevitably, like so many other things, it was postponed; today, after seven months of sessions, the workshop has morphed into an extended, intensive experience that only could have been possible online.

The materials sourced and provided to the nine participating artists gave rise to collaborative projects, and to topics of debate: audiovisual archives from Syros such as super 8 home movies from the 1960s, a collection of contemporary sound and field recordings, as well as Egyptian material including found footage, a Jesuit collection, a news agency archive and newsreels spanning the greater part of the 20th century. The dismissive tone of a British journalist, narrating a bustling city scene in Cairo, brings the uncomfortable specter of colonialism into focus; field recordings from Syros, provided in unclassified folders with no explanatory information or metadata, ask us to guess their provenance and re-envision their potential uses. Taken together, our collected screen recordings, group chats and web histories constitute an evergrowing logbook of daily experience; our desktops themselves become miniature, personal, digital archives, held at arm’s reach. Cinema, ever a mirror for technological and historical change, settles uneasily into these new confines alongside us.

I linger on an image: the setting is Syros, sometime in the late 1960’s. A group of kids bop heads and jostle with one another around a portable record player set up on a marble block in the middle of a grassy field. A boy strums at a rake, a girl brushes a lock of hair from her forehead as she sways intently to the inaudible rhythm. It looks like another clear, sunny morning. I think of the cameraman’s urge to capture this scene, of a beaming gesture from Stefani’s film and of Lynch’s insistent predictions of the weather, holding these moments like a talisman for the storms to come.

1. Penelope Koliopoulou, Red Light District, Amsterdam, 2020, video still, Less than 300 dpi, 3 13 2. Screenshot from @daily_lynch Instagram account 3. Joseph Hepp, Villar’s adventures, 1924, 24’, film still, courtesy of the Greek Film Archive

*Jacob Moe is a documentarian, archivist and translator. He is co-founder of the Syros International Film Festival, and founder of the Archipelago Network. Jacob was part of the ARTWORKS Moving Image Selection Committee 2019 along with Maria Drandaki and Angelos Frantzis.

**Τhis text was part of the 2nd publication of ARTWORKS that reflects the SNF Artist Fellowship Program 2019-2020