ON VIEWERSHIP, THEATRICALITY, ANGER AND OTHER STORIES OF TRANSFORMATION

There’s something in Antonis Pittas’ practice that still remains wilfully undefinable, lingering in between linear, historical, modernist, clean and perfect visions, reflections and reenactments of reality, of time and space and everything these ethics and aesthetics bring along and (here comes the oxymoron), the epitome of vulnerability, clumsiness and fearlessness when facing aspects for the unknown, when finding a language for the dirty, when speaking history otherwise, tracing its links and chasms. Through his work, the emblematic, bravely looks downwards, the trivial turns into a mechanism of resistance, the demonised metamorphoses into a kinship protecting the wounded.

To me, it all sounds like poetry.

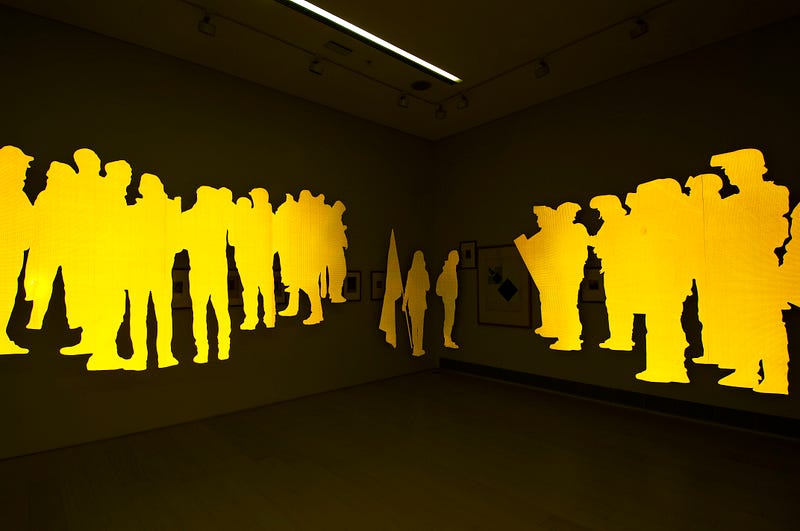

Ioanna Gerakidi: I’ll start with something you once told me, like 10 years ago, which still comes to my mind every now and then. You said that I should be careful because people sometimes can get lost among the inbetweens, referring to both professional and personal decisions. And I think we can agree that these decisions are also, or least partially, ruled by psychosocial factors. Now, what I see in the ways that your practice evolves through the years is that you stay with the in-betweens. You give them the time and space they deserve; from the ways that movements formed in the interbellum period -like the Bauhaus or the Russian Avant Garde- are engraved in your practice, to the methods you find to trace resistance within an institutional context, like you do in your exhibition “Jaune, Geel, Gelb, Yellow” at EMST. It feels like you willfully aesthetise what’s seenas dirty or challenging in order to undemonise it, to me at least.

Antonis Pittas: To answer your question, I’m actually kind of stuck in this in between. And I think this gray zone or the things that are not really graspable, spatially and otherwise, in personal or in collective ways, fascinate me. Because this is the exact space and the time that people need to transmit themselves from point A to point B, to turn information into knowledge; and that needs time. That transmission also implies several emotional and social factors; it’s a multifaceted in between.

So, yes, the difference is obvious when speaking about and looking on historical movements like the Russian Avant Garde or the Bauhaus. These movements allow you to see space and time as historical evidence. So, looking at and looking back-becomes a source of a knowledge. And then on movement: movement is something that is happening, or at least it implies something that once happened and was archived after. Regarding this show, I was living in Paris when this movement was taking place in the city. When you are in the middle of something, you don’t always have the time to stop and think about what’s happening around you, you just react to it. And that’s exactly how I felt.

In these cases, you don’t have the luxury of time, which is also something that intrigues me. What does it mean to take the risk, to pause something and “historicize the contemporary” in a certain degree? I’m picking up that expression because it’s quite important in my research. Recycling history is a very big part of my work. Contemporizing history is, at least to me, a methodology. What I’m trying to do is to historicize the contemporary, having in mind the knowledge that I got from previous movements, with their aesthetics being part of that knowledge.

I’m very aware that my work deals with aesthetics and that holds a great risk. In my practice there’s something contradictory, because realistically I am looking for something which can be regarded as abstract, yet it does have very specific dynamics. So, the work needs to be sensitive and able to be respectful towards its subject.

Aesthetics is a means; it’s the visual form through which I can communicate these complexities while showing respect towards them. Aesthetics obviously are within me, but I’m trying to challenge their limits and connotations; aesthetics is being formed always in relation to the aesthetics of others, in this case in relation to Theo Van Doesburg’s, a recognized and established artist. Things are always in relation to one another, and I don’t think anyone, including myself, can escape from that. I am not sure if I replied to your question.

IG: You did. And I think that this is also very genuine, because through what you call “historicizing the contemporary”, you’re transcribing something that comes with the masses, from a demand, a practice of anger or resistance; and in a way you kind of offer it back to them, for approval, rejection or just for reflection. And you do it through a contemporary art form, which has the tendency to be exclusive, at least when considered as Avant Garde. So, to me, your contribution is generous, it’s inclusive.

AP: Exactly. This idea of historicizing the contemporary and contemporizing the historical — this is a mutual relation — is one of my work’s axis on which I focused, a couple of years ago, when I was an honorary fellow at the University of Amsterdam. Τhese are cycles that are not excluding one another, and these exact cycles allowed me to “borrow” these forms, methodologies and linguistic systems. If you look back at the Russian Avant Garde — and I’m sorry if I keep going back to this, it sounds very old fashioned — you’ll see that the artists affiliated with that movement, researched and aimed to create this form of utopia to capture that moment (as the momentum) of their era. How can the “new” be captured, what does it mean, what can it bring or which kind of forms it takes, is what really engages me. Also, how this can be done, especially when you are “inside the box”. How can borders be captured, in a formative but also in an intellectual way? That’s what my practice is partially about.

IG: I think we’ll come back to that, as there’s more here, in terms that creating a form is also part of your language. But going back to the contemporary, how did the use of Instagram come to you? As a mechanism of activating the work otherwise? Or outside the museum walls? I assume that this was a deliberate choice of yours? It made me think of how Kracauer looks at and with the masses; he says, paraphrasing his words, that it’s through the surface, the triviality and the ephemerality of the masses that modern life can be understood.

AP: It’s very difficult to disagree with his words. And actually, I am using this other space through this activation. To be honest, I don’t use Instagram that much, I am there, I am following the waves coming with it and its psychosocial applications in our realities, the parallel spaces it can create in terms of how we communicate with others about current, political or personal subjects. Instagram creates parallel spaces in ways related to how we pose or share an image; it makes you a viewer. The position of the viewer, is what really interests me; and the four walls of a museum put you in the exact same position, that of being the viewer.

What I do, or what we do as artists in general, is that we make an image, sharing the personal while being part of the collective. It’s up to each us what we’ll choose to share with the viewer. The viewer, also performs an image. And when it comes to this work, it all starts with me being the viewer. I was just a witness of the protests of the yellow vest movement; I was capturing the moment and I guess that’s what I wanted to state with the gesture of utilizing Instagram as a mechanism for re-activating the work: to make space for capturing and for sharing. In that way the viewers are part of “the evidence”, the archive; they reactivate the archive, or they could so in a way, at least potentially.

Media can open up discourses, even though, they do have a certain toxicity. The colour of the work itself (yellow) implies such a toxicity, when affiliated with the media. But this is exactly what the viewer can reverse, when they stay with the image and when they choose the ways in which they re-enact the discussions around the work or the movement.

The agency each of us has as viewer, in terms of sharing an image, is very important; it comes with responsibility. I am responsible for making my work, I’m responsible for the ways I position myself inside and outside my artistic practice. And I want to have an equal relation with my viewer. They do own their responsibility towards it, towards their perception, or their ways of enacting it. I can’t force the viewer to do something. That’s a choice. And at the same time, I am aware that I cannot control the results, how the viewer will share or even look at the work.

IG: I’ve read another interview of yours and you refer to your work as being or becoming a stage, if I remember well, which to me, makes total sense when it comes to the various and multifaceted forms that your installations have taken in the past years; I mean sometimes you enter the space and it feels like you are exposed to the props of a play, or like you’ve been given the permission to be part of it. And it makes me wonder, if seen as a stage, if touched or sensed as a stage, what does your work host or trigger or reveal or cleanse?

AP: The space could be regarded as a stage; there is obviously an element of theatricality through the architectural or choreographic qualities of the work. There are several trajectories intertwining when working with the “arrangement” of objects. And then the ways that narratives or subjects unfold within these trajectories, or the ways that movements have used the camera or the flash in the past as elements for creating a certain dramaturgy through them, is also something that brings in a certain theatricality. The use of the reflective material, the connotations of graphite or the subtle ambience of dirtiness, are all elements that serve a specific purpose. And that is again an extra piece of the puzzle of the work, which could potentially make the viewer a protagonist; they have to make decisions on how they will navigate themselves through all of these qualities. And this is one of the reasons why I am always within the work when it is still in progress. And this is also something that I observe when I am visiting exhibitions myself. The viewers can undertake a specific role and it’s up to them to do it.

And then there is also a theatricality that comes with the ways you can enter a show. If you think about it, you have two different entry points. There is not only one way; the narrative then is a priori not linear, or at least it doesn’t have a sole reading. The idea is that every time can be different, and it’s up to you as a viewer to find your own logic, to understand, to grasp the work your way. It all depends on your trajectory. And exactly the same goes with the way you walk in a demonstration, right? It could be that you enter when a violent episode occurs, or it can be very peaceful, or it can be that you are late and it’s almost done. And every time there is a different street where the demonstration happens, a different city etc. But still, within a demonstration there are some specifics. The same specifics are present in a show, in theater play or in any act of dramaturgy, they are there but the ways you’ll be navigated through them is up to you.

And there is also another type of dramaturgy, when there is an exhibition within a collection exhibition, like it goes with museums sometimes, which is like a surgery; a narrative within a narrative, like ancient tragedies you know? And you can borrow this narrative, feel through it, which is a beautiful moment. And this exhibition does that, it turns into a “live space” where narratives co-exist. And it’s interesting because, there are exhibitions, efforts, curatorial, architectural and of course artistic decisions that bring oxymoronic schemes together. Works from different eras or movements, like the Russian Avant Garde, which was extremely political, or De-Stihl which was refusing to be political, find themselves in the same “wider” narrative, creating an intellectual discussion about aesthetics, balance and synthesis, and while proposing the new, are almost impossible not to be political.

IG: Whilst talking about the stage, you brought up theatricality and dramaturgy which inevitably brings me to the dramatic quality of your work — when thinking of drama through its etymology- coming from the verb “δράω-δρώ”, which means “to move”. I mean there is definitely a movement in your work, through your spatial decisions, colour palettes, use of frames, patterns, pictures of your parts of your body, that to me very much resembles to a choreography. Not in a lyrical, linear sense though. In a way of writing the space otherwise and/or creating a “mise en abyme”, a narrative within the already existing one.

AP: The idea of drama. The work deals with sensitive subjects; both the subject and the implementation of the work did have a certain impact on me, they moved me in a way. So, I guess, there is something “moving” in the work, an experience that moves you, a position that can possibly change through this experience, both for me as a maker but also for the viewer. The colors, the forms, the materiality also have a certain movement. The materiality for sure has the weight of movement, the totality of it does have a connotation of movement or drama.

So, all the things are coming together to serve that purpose. All of the decisions are actually made to allow a certain movement. Yellow for example, is one of the colors that has been massively used in modernity, tracing aspects of the contemporary and the movements coming with it, literally and metaphorically. Another aspect — that “serves” this moving purpose, this idea of drama, is the strong fluorescent quality of the color which feels like it can hurt your eyes. Τo me there is something comforting there, that comes with the familiarity that the viewer has with the color, and something discomforting coming with the sharpness of the fluorescent quality of it.

IG: Speaking about spaces and narratives, I would like you to tell me a few words about the use and roles of archives in your work. There is a part of them that becomes part of the work sometimes, like the quotes you used in a past series of works and it engages directly with collective histories or the collective unconscious. And then another part, which is more subtle and it traces your autoethnography, an archive of your agonies, desires, failures, successes.

AP: That’s an interesting question because you can’t really separate these two things, the collective and the personal I mean. The collective affects the ways we look, focus, interact and reflect on aspects of our personal and social lives, even forms sometimes the things we want to do or that we avoid doing. Someone, I can’t recall their name now, was talking about the “archeology of the new”, which allows for tensions and oppositional schemes; like the essence of when things that are new, come together with what’s regarded as old. Archives have always been part of my research focus or my work in aesthetic terms. There is something dusty in them, an unrevealed story, which has its own potency.

The narrative of time is what the archive opens up. Because we do have this need to capture, to preserve memory or information or history, which fascinates me in one hand, yet also makes me angry. For me, digging into archives, “waking them up” is what I name the contemporary moment. So this idea that the archives are there to restate themselves within the contemporary reality, is quite crucial in my practice, because some narratives of the past are very similar to current ones; it’s a cycle though it’s never the same.

And that’s where language comes in, the familiarity of language, the familiarity of form as a language, which allows me to work on new narratives that come with time whilst recycling the past ones. And the past ones are not necessarily similar to the new ones; sometimes they are extremely oppositional, when thinking about the same subject now and then and the ways it’s represented in a critical way nowadays — compared to some decades ago. And of course, archives have their own aesthetics and smell, and I find them attractive because of that. Without aestheticizing them though, as many of them come with pain and fear; yet, the word objection or the word resistance or vandalism appended on narratives of the past is very important and the legitimate anger coming with it is also something that I’m thinking about.

IG: So, let’s say that you wake up one day, you listen to the news and the world is ending. What would you vandalize? And what would you save? (It could be anything, from a feeling to a note to a space, just say the first thing that comes to your mind).

AP: It’s very difficult to answer this question, especially thinking that the world is ending. I don’t know if I would have the need to vandalize something then. But, if the end was close, I am thinking that I would try to vanish whatever is very valuable, to me at least. And I guess it all rotates around the idea of value, and I guess this is exactly the reason why there are many times — when I deeply understand why a piece of art or a monument has been attacked, only because they represent something very specific, which varies but still. I find it interesting; the need of someone to express their political or personal emotions, without dichotomizing them, in such a violent way.

How could someone react when someone or something makes them so upset, that they have the urge to attack, to stand up their right, to hate. This emotion is to me what vandalizing is about. And the settings, the broken pieces, the ruins of this vandalizing act are something that my work aims to trace. This evangelistic moment that the narrative of vandalism comes, that makes the object, the outcome, the ruin one thing and vandalism another. How can you see a monolith without thinking that has once been vandalized; which is very much a stupid example, but did I make it clear?

IG: Yes! But when you say, that you would vandalize whatever is valuable and then you’re speaking about this new life, this new object, this new entity that appears after surviving the act of vandalization. And you are referring to objects, to monuments, art pieces. What about agonies, feelings, all the immaterial things that are valuable? Would you vandalize them as well? To allow them to go through a transformative process, to let them have an afterlife? And would that be equally cleansing?

AP: There, yes, I guess, I’d let emotions become something else. I will give you a small example. When the big demonstrations were taking place in Athens, some of the demonstrators were carrying a hammer. They were destroying all the staircases around them and they were using the broken pieces of marble as weapons after; or at least as tools that could potentially harm the police. This transformation, of both feelings and objects, it was an act of resistance. It’s very interesting that important buildings in Athens, historically, architecturally, emotionally, symbolically have been vandalized. The idea that, at this exact moment, the impulse let’s say, is not saying “there’s an important building in front of me” but instead saying “that’s a stone, and if I just break it, I can throw it, or throw it back”, is an act of resistance. To take this one step further, it’s interesting that the process of thinking an immaterially valuable thing is absent and that the value of the immaterially valuable thing is also absent.

If someone decides that they want to vandalize something in the public space, it’s because they want you to feel hurt, they want to force you to hear them, pay attention to them, they want to punch your stomach, wake you up. It’s interesting how you reach a moment in life that you feel that urge; I once proposed at the Stedelijk Museum a work that would be about that, it was like a dream; I wanted to take a hammer and break the main staircase of the museum. And on this exact staircase, performances by Gilbert and George, and many other known artists took place; I mean it is used as a performance space. My Dutch colleagues were totally upset, they thought of this gesture as something ridiculous. However, why would it be ridiculous to break the symbolic staircase, which anyway, you are going to fix after. And I understand that such a statement can make many people angry, and perhaps I shouldn’t say that, but yes, fuck art.

As a human being I am allowed to address that, there are things outside art, or that things that through art can be spoken otherwise. And we have a war, don’t forget that. What’s happening around us, socially, politically, historically, it’s all very fragile. And the moment you can finally be heard, the moment that someone really listens to you when you are screaming, is very valid.

But then again it depends on the context; Greece and the Netherlands have huge differences when it comes to how these needs or desires or acts are performed. And it’s because of these cultural differences, that these acts make sense only within their context. I can’t image such a scream in the Netherlands, the same way I can’t imagine staying calm in Greece. You need to understand these societies through a series of facts, like history, performing history, performing realities but also surroundings, landscapes, or even the quality of the air. It’s so multifaceted what allows us to listen to one another.

IG: Tell me a short story about transformation. If you don’t know any, make up one please.

AP: I just did. That was definitely a story of transformation. The broken marbles and the differently structured patches in Athens. It’s all historical and it all has its own value. I recently took pictures of “scarred” buildings from the Civil War and the second World War, where there were traces of bullets on them. I really want to do something with them at some point. However, I am not fetishizing these materials; I’m not overvaluing them either and it’s important to mention that. These are all violent acts, and I am not in favor of violence. Violence, is another story.

Antonis Pittas (1973, Athens, Greece) lives and works in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. He studied at the Athens School of fine Arts; the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam; the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam. Pittas has been an artist-in-residence at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York; and has been a Honorary Fellow of the Faculty of Humanities, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam where he researched and produced work under the rubric ‘Recycling History (contemporising history/historicising the contemporary)’. Recent and forthcoming solo exhibitions have been held at EMST, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens (2022); Centraal Museum, Utrecht (2021); Van Doesburg House, Paris (2020); Significant Other, Vienna (2019); Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam (2018); Hordaland Kunstsenter, Bergen (2017); Narrative Projects, London (2016); Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam (2015); State Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki (2015).

Antonis has contributed to group exhibitions at Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Riga, Latvia (2022); D&A by V&T, Lisbon, Portugal (2022); EMST, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens (2022); Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam (2021);State Hydrometeorological Institute, Skopje (2020); MOMus-Experimental Center for the Arts, Thessaloniki (2019); Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje (2019); Manifesta 12, Palermo (2018); MACRO Museum Testaccio, Rome (2017); BAK, Utrecht (2017); Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (2017); Onomatopee, Eindhoven (2016); Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow (2015); 5th Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki (2015). Public commissions have been realised for Significant Other, Vienna (2019); Art in Space, Prague (2018); de Appel, Amsterdam (2018); Kunsthal Extra City, Antwerp (2017); and the 4th Athens Biennale (2013).

Pittas holds a tutor position at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague. Previously Pittas tutored at the Design Academy Eindhoven and Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam and was guest professor at Hildesheim University. He has been a guest lecturer at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam, the University of Bergen Faculty for Art, Music and Design, the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, and the Bard College in Annandale, New York.

Ioanna Gerakidi is a writer, curator and educator based in Athens. Her research interests think through the subjects of language and disorder, drawing on feminist, educational, poetic and archival studies and schemes. She has collaborated with and curated exhibitions and events for various institutions and galleries and residencies and her texts and poems have appeared in international platforms, magazines and publications. She has lectured or led workshops, seminars and talks for academies and research programs across Europe. Her practice and exhibitions have been awarded by institutions, such as Rupert Residency, Mondriaan Fonds, Outset and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) Artist Fellowship by ARTWORKS, amongst others.