RE-ESTABLISHING THE HORIZON – THE COORDINATED BEHAVIOUR OF THANASIS CHONDROS AND ALEXANDRA KATSIANI

The way Thanasis Chondros (1953) and Alexandra Katsiani (1954) speak about their joint artistic work, which officially began in 1981 in Thessaloniki, always feels like a direct continuation of that work – or even like an artwork in itself. The intuitive manner in which they move from one issue to the next, the historical references that slip in, the driving rhythm, and, finally, their recurring focus on the everyday as their primary point of reference render language an integral part of their practice. Thus, although they ceased their artistic production in 2004, one could say that through their discourse, they continue to expand their indivisible universe, along with its sensory codes of perception and rhythmic intensity.

Indeed, from the pirate radio station they set up in 1985 – broadcasting texts on art and music – to the magazine Bitoni, and from their poetry to their work as Greek language and literature teachers, language has consistently functioned as their fundamental material.

Writing about Chondros/Katsiani is therefore no easy task, and one that perhaps flirts with the risk of “curatorial guidance,” a danger they themselves always believed lurked in the background. For this reason, the present text unfolds interstitially, in the margins and cracks of their own discourse and thought, with the invaluable contribution of the ISET archive as a research tool. A text about Chondros/Katsiani ought, in some way, to be theirs, written in a language that belongs to them.

Chondros/Katsiani, From the project Cutting–Sewing, Thessaloniki, 2004

“We assume that what happens with every couple, when they become a couple, is an effort to coordinate their behaviours. It’s not simple; individual quirks must be smoothed out, and then a shared daily life must be organised, both as a couple and within a broader environment. This happens to everyone; we simply articulated it with greater or lesser emphasis in various cases. Everyday life is the hard core of existence; it appears repetitive, yet in reality it is permeated by diverse currents, at an ever-increasing pace since World War II.”

With a torrent-like yet always sensible manner, and by incorporating the legacies of World War II into the design of conjugal life, Chondros/Katsiani approach not only the nucleus of their practice as a “coordination of their behaviours”, but also propose this position as an alternative to dominant conceptions of art. For them, “behaviour” is synonymous with everyday life; consequently, the immediate and untranslated everyday becomes the essential substrate for what can confidently be described as one of the most experimental and independent performance practices in Greece.

Even the later, deliberately literal name they adopted in 1984, together with Danis Tragopoulos, Civil Servants’ Penthouse, attests not merely to the infiltration, but to the full identification of their daily life with their art.

Chondros/Katsiani, Participation of the Brotherhood of Immaculate Liberation in demonstrations, 2003

“What everyday life teaches is the indivisibility of existence. The expansion of the perception of the everyday, the grasp of its multiplicity, and its socio-political dimension were what pushed us to leap from the position of the audience to that of the creator. For methodological reasons alone, we divide everything into sectors and categories, but experience is unified; consciousness accepts everything as a whole – the heroic grandiloquence of the post-junta era and the sense of dramatic impotence surrounding the Cyprus conflict, the well-cooked meal and the poorly phrased expression, the atmosphere of freedom and the persistence of various stereotypes.”

Current events are approached as collective everydayness and play a significant role in their work. In one of their final performances in 2004, on the day of the national elections, they sewed garments for themselves and attendees out of newspapers, while tapes of campaign speeches from the 1980s played in the background. In 2003, the group Brotherhood of Immaculate Liberation / 3A, which they had formed two years earlier with Hector Mavridis and Iordanis Stylidis, was activated during the American bombings of Iraq and participated in demonstrations demanding “the re-establishment of the horizon, of perspective, and of the future.” In these instances, the relationship between everyday life and art for Chondros/Katsiani becomes evident and is most succinctly encapsulated in the notion of behaviour.

Chondros/Katsiani, One Last Meeting, A Few Images to Remember, within the framework of Hyperdothe, Thessaloniki,

2004

“We wrote about choices of behaviour; let’s clarify with an example. Art galleries close during the summer, which is something normal for dealers, but not for art lovers. We said: let’s operate a space precisely during the period when commercial galleries shut down. That’s how Schedia came about in Thessaloniki in 1983. What else prompted its creation? The importance of the frame of reference and of flow. Once again, these are simple observations, arising from everyday experience: How does a good broadcast function within the continuous flow of a lousy TV programme? How does a poignant artwork function within a polished, gleaming space?”

Schedia was founded in the summer of 1983 and was deliberately short-lived, creating a meeting framework for the artists themselves, the public, and other creators. As is often the case, independent practices are born and incubated in some degree of relation to institutions, and subsequently find themselves continually negotiating how close they should remain to them or how far they should stray. Throughout their artistic trajectory, Chondros/Katsiani continually fostered this space between themselves and institutionalisation.

“It’s crucial that we weren’t trained to become artists. We escaped the exhortations to develop a ‘personal language’ or an ‘artistic vision.’ Nor did we intend to be labelled as artists; it was simply choices of behaviour within the chaotic everyday landscape that brought us there. In the early years, we felt embarrassed whenever we were called artists or asked to sign something. We eventually accepted it, since over time our refusal would have seemed pretentious.”

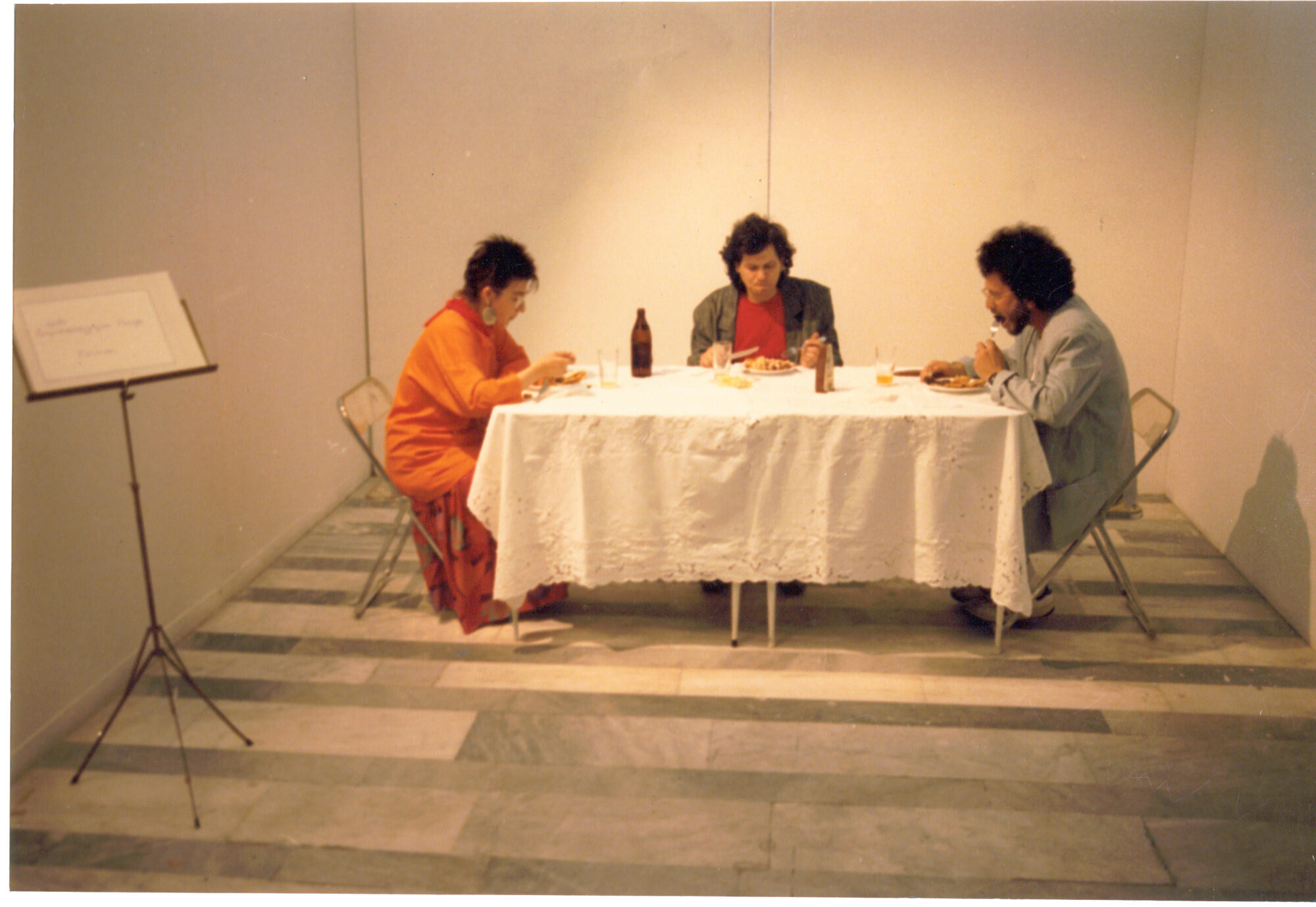

Chondros/Katsiani, Words Are Bridges, an action in the programmatically short-lived Schedia space, Thessaloniki, 1983

Chondros/Katsiani, Logo of oikoi publications, Thessaloniki, 2018–present

They later continue:

“We said we weren’t trained to become artists, but we were trained to observe, analyse, and critique. One could say we were trained as an audience. Performance has a characteristic that other expressive modes lack: someone can paint for pleasure, play an instrument to pass the time, or write poems for the drawer, but performance does not exist without an audience. The audience lies at the centre of performance. We respect the audience; we respect the filter of its personal needs and experiences through which a work is received one way or another. We do not particularly value guidance, which often turns into manipulation, on the part of many curators.”

Given their focus on the audience and the way they imagine it as inseparable from their actions, it is worth noting that one key “interlocutor” who greatly nourished their practice was the students at the schools where they worked.

“We must stress the impact our work in schools had on us. You can’t fool children. Adults are often trapped by a couple of quotations from an author they don’t know and don’t want to admit they don’t know. Students, by contrast, do not hesitate to reject what fails to convince them.”

I wonder what a Chondros/Katsiani performance might look like today, given their own observation that technological developments have shrunk spaces of encounter while expanding the domain of spectacle.

Chondros/Katsiani, Shortly after the start of the mountain running race with the group of Anonymous Rationalists, Kipoi Zagori, 2017

“Public space is privileged for the presentation of performance, especially when unannounced, because the action takes the form of an encounter. In everyday conditions, the audience comes face-to-face with something that disrupts habit, providing stimuli for thought and feeling. Today, however, with the ubiquity of mobile phones recording everything, every action tends to be reduced to spectacle, whereas in the past there were actions that remained entirely undocumented.”

Despite the importance of public space, the home – the personal, domestic sphere – also plays a prominent role in their work. How could it be otherwise, in a practice that so emphatically embraces the value of the everyday; in the case of two artists with such a coordinated spontaneity of behaviour, and of two working parents without imposed limits on their artistic means? Yperdothe – a term opposed to “Beyond,” describing not the metaphysical, but the everyday – consisted of daily presentations of works in their apartment in March 2004. The pirate radio station and alternative art space Schedia were likewise broadcast and organised from the same location. Today, the publishing house oíkoi (the adverb, with smooth breathing and acute accent) literally means “at home,” signalling an intention to frame whatever emerges from family play.

Chondros/Katsiani, Virtual conferences (symposia, one-day conferences): one poster, Thessaloniki, 2019

In a 2021 interview with Kostis Kilymis, they write:

“In the end, perhaps we didn’t phrase it as we should have. We said we were abandoning artistic creation, whereas it would have been more accurate – though admittedly vague – to say that artistic creation is no longer part of our behaviour. From the beginning, what interested us was behaviour as something total.”

The coordination of their behaviour, however, as expected, continues: with the group Anonymous Rationalists, formed together with their children, through which they participate in mountain ultramarathons and organise virtual conferences such as “Malice as a Result of Climate Change”; through the poetry they continue to write; through oíkoi and oíkoi 2310; through Civil Servants’ Penthouse, which remained active until 2006; and through so many other coordinated and uncoordinated behaviours that will persist in their public and private spaces and lives, with or without our knowledge.

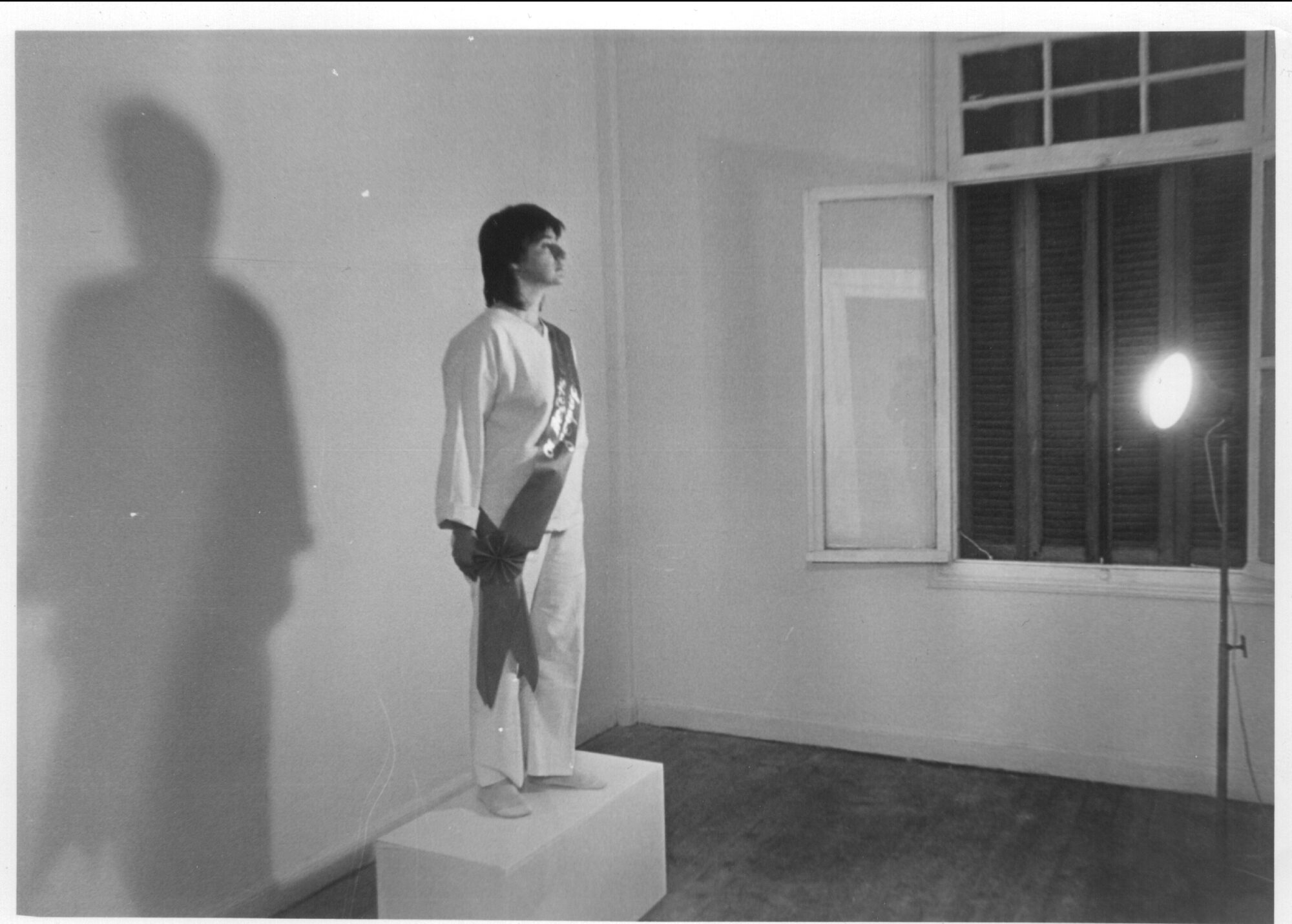

Chondros/Katsiani, Action entitled Rule, by the Civil Servants’ Penthouse, within the framework of the Panhellenic Exhibition, Piraeus, 1987

*The starting point and compass of the above text is the archive of the Institute of Contemporary Greek Art (ISET) and the research conducted within it. Initially aimed at understanding and mapping performative practices in Greece from the 1970s to the present, I encountered numerous research obstacles, most of them stemming from the absence of documentation when such actions took place outside institutional frameworks. The practice of Chondros/Katsiani emerged as one of the most compelling examples within my ongoing research, shifting the focus of this text from summarising available sources to producing new knowledge with the direct contribution of the involved artists. The research – and, by extension, this text –seeks a reciprocal, nourishing relationship with the ISET archive.